Manfred Schmidt With Mrs. Meier in the Desert by Manfred Schmidt

This is a sort of travelogue that seems to be based on the author’s own experiences around the world, the first leg of which takes him through Venice. It’s meant to satirize a number of different things, some of which are beyond my understanding of German culture of that era. The author did serve during World War II, but it appears as though he didn’t see any action and mainly worked in the ministry of propaganda on the eastern front, so I don’t plan on holding it against him too harshly. Having looked through some other materials it doesn’t seem as though he was personally antisemitic, but I understand if parts of my audience choose to skip over this week’s article. The rest of you are welcome to check out the animated German children’s TV series created from his comic strip characters (after reading this, of course).

Chapter one: Venice Firmly in German Hands

Looking through just the right angle of the alleys behind the Munich Hofbräuhaus, one can nearly see Venice. At least, that’s how certain Germans living north of the river Main feel about the world below them. The Germans, well-known for their creativity, conjured up an itinerary that would take them from Munich to Venice in two days, with ample time for sightseeing, postcard-writing, and window shopping. That would leave just enough time to return to the office on Monday morning with glazed-over eyes, but the feeling of the Alpine breeze still blowing through one’s mind.

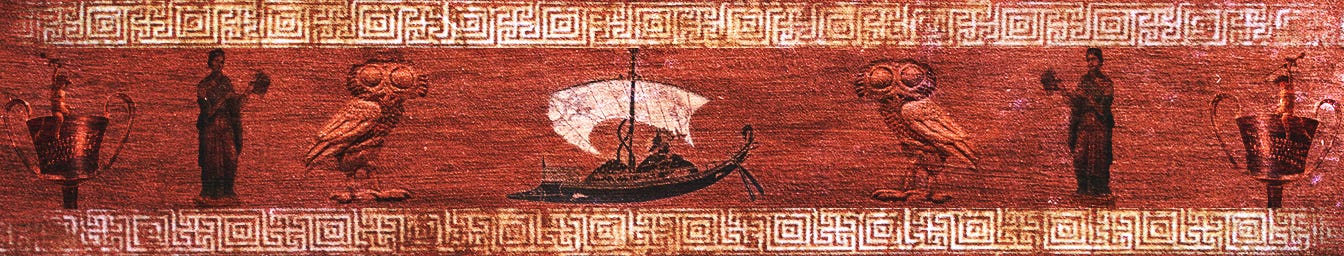

For the sake of my Northern readers, I have taken one of these so-called “Weekend Crusader’s Race” to Venice and back. This name must have been chosen because of the class of licenses and engine capacities of the South German drivers. The path roughly follows the journey of the crusaders, who began their journey a few hundred years ago and invested all their financial resources (as far down to the shirts off their backs) in the Venetian banks before they went on their journey by ship to the holy land.

An old chronicle reported that in the year 1096, a combined force of seven thousand departed together from inside the modern boundaries of the city of Venice, only two thousand of which eventually returned to their homeland. This rate of loss along the path has decreased significantly, thanks to innovations in road safety despite the invention of the motor. The only thing that has remained 100% consistent is the Venetians’ exploitation of foolhardy foreigners.

If someone were to set off early on a Saturday before the dew set and the daylight broke, they would only encounter a little traffic and make a lot of forward progress in a short amount of time. This chestnut of wisdom seems to be universal, because by the time I had set off at 6 a.m., Italian drivers who hadn’t slept enough and skipped breakfast had already formed long columns. The heads of the families usually forbid pit stops for coffee or breakfast on the way, because every hour spent off the road costs them another two or three miles. Furthermore, a trouble that plagues the mind of every traveler is that the car in front of them may snag the last available parking space and the last free hotel room in Venice, which is why they will go to desperate lengths to overtake anyone. They will even cross the dividing line in the most harrowing mountain passes, because they cannot fathom who would be traveling in the opposite direction on a weekend like this. On the return journey it was completely reversed, as if nobody had any reason to travel to Venice during the work week. The border officers at Mittenwald moved with such uncanny precision that every five seconds a car would be permitted to pass. The word “control” could not be better represented anywhere else.

After a few more miles, the route took us up to Zirl mountain, and I read what must have been the only traffic sign in all of Europe to say “in the next two miles, beware of odor!” That mysterious sign was a good way to make conversation all the way till Innsbruck. There, I was happy to see the famous “Golden Roof” in the rearview mirror, because it meant all the sightseeing tourists would waste their time there.

The sign “Brenner Pass in 15 miles” made all the drivers step a little harder on the gas. The tempo of the traffic became much quicker. The reason behind this was probably the rumor that Venice’s days were numbered because of the waves constantly breaking against its foundations.

Maybe it’s an exaggeration if I claim that the speed of the colony of vehicles in the last thirty miles to Venice is set by the rate at which they find parking places for the lagoon.

Venice’s biggest disadvantage is that travelers cannot simply drive their cars to the restaurants and hotels. Even as a German, you have to leave all that you cherish outside of the city. The prestige-driven federal bureaucrats, however, save face by calling out to their companions in the hotel lobby and everywhere else where there is enough of an audience, with a room-filling voice “Our new 220 S marches bravely!” That way, everyone else in the area knows that the man is selling something.

Once someone has found a parking space and finally boards a crowded boat to cross the Grand Canal, they will be overwhelmed by the photo opportunities. If you don’t take advantage of the complimentary viewfinders, you’ll lose a lot of money to the photography or the postcard industries. From the S-boats full of tourists, a volley of snap-shots fly out like a cannon barrage. On especially beautiful weekends, conservative estimates say that around 30,000 pictures of the Rialto bridge will be taken daily. The sense of ownership and personal property that is so highly developed in our time causes everyone to take the same picture that they could easily get for twenty cents on a postcard, rather than on film.

I don’t want to say anything about the search for the hotel. Everyone is accommodated. If the hotels do get sold out, the porters will put them up in the so-called “private beds.” This neologism refutes the notion that all the other beds should be something private.

After putting down the bags, there is only one goal for the patrons: visiting St. Mark’s Plaza. Before dawn breaks, every amateur photographer worth his salt wants to capture a scene of the famous pigeon-feeding. All of them have in mind the same image of the pigeons fluttering through the crowds of people to the north, landing on every free hand, head, and shoulder to pick greedily at the breadcrumbs.

Think of it!

In the afternoon, the pigeons have been overfed through the morning and apathetically drag their pot bellies over the ground, not willing to turn their backs just because of a scrap of food. They no longer look like pigeons, but rather resemble bald-headed laying hens. They wear the facial expressions of successful captains of industry.

The lovely little animals won’t wake up again until the next morning. The food, meanwhile, gets turned into a grayish-whitish paste that falls on the buildings and shoulders and hats in the square. Concession stands fill up bags of popcorn to ensure that photographers are stocked up on fodder to achieve that one perfect shot. For a dollar, you can get a half-cup of popcorn. According to my preliminary estimates, they eat at least a hundred pounds of the stuff throughout the day across those small portions. The popcorn, having been given either to man or to pigeon, brings in around $4,000 a day, while the raw ingredients cost the proprietor no more than $150. With such a high profit margin, every German loan shark’s heart must beat faster. If my eyes did not deceive me, I swear I saw one of the pigeon food salesmen one evening motoring up to the plaza in a sleek new fishing boat.

After visiting the pigeons, tourists can quench their thirst for cultural enrichment with a quick tour of the Doge’s palace. This sightseeing destination generated a painful feeling in my neck from all the beautiful ceiling art. Luckily, a quick visit to the low-ceilinged prison vault evened things out.

For the rest of the afternoon, people generally spend their time in various gelaterias and cafes so they can speak about the conditions of the local businesses. These conversations, however, are often interrupted by an outburst of “Look over there, isn’t that…” inserting the name of some acquaintance at the end.

Most of the time it isn’t, but occasionally they do see someone they know. Then, a wave of endless laughter and awe of recognition begins. In every corner of Venice, the conversations are marred by the same inescapable rhetorical question “Oh, are you also here?” Occasionally it’s nice to know that others can see that you’re in Venice, but that can dampen the feeling of exclusivity in your expensive getaway, too.

In the late afternoon, St. Mark’s Plaza is firmly in the hands of the Germans. Individual Allied shock troops occasionally attempt to move around here and there in certain corners of the plaza, but very quickly flee. The Americans retreat to “Harry’s Bar,” where they are guaranteed to find their cherished whiskies and gins. The French systematically comb through all the streets until they find a posted menu to inspect carefully. The British mostly stay in their hotels and drink tea. Only the German-speaking Italians hold their positions and offer their wares: postcards, watches, jewelry, lace doilies, and services of every kind.

I was so happy. A really nice black watch was on sale. Although I knew there must be some kind of trick, I couldn’t find a reason to refuse the salesman. It was, of course, the oldest trick in the book and yet it still finds new victims every year. So that my readers who may want to visit Venice in the near future will not fall for this scam, I want to describe it in detail here.

In a discreet whisper, the con man offers a stranger a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity: a Swiss-quality watch for only 90 Deutsche Marks! Then, a gentleman (clearly disguised as a fellow tourist with his floral shirt and camera hanging from his neck) pushes his way into the conversation, warning the victim, “Don’t buy the watch! This is all garbage! They’re all fraudsters! Look here…”

He then snatches the watch out of the con man’s hand. “See, I’m a watchmaker by trade, and…”

He opens the back of the watch with a deft motion, and his eyes widen. “Hold on a second, I can’t believe it! This watch is worth almost six times that price! What could this tramp be doing with it?”

The “tramp” whispers in an embarrassed tone: “100 Deutsche Marks!”

The “tourist” now begins to scratch his head, saying things like “that’s really a generous price! Oh, if only I had that amount on me… buy it for yourself! That watch wouldn’t go for less than 400 anywhere else!”

What most people don’t realize is that the tramp, the tourist, and the original stranger are all part of a crack team of scam artists. The watch, in truth, is worth no more than 30.

Readers may ask why I did not merely call the police when I realized I’d been tricked. It would have been pointless in this case, because the tramp always makes sure to carry a second, genuine Swiss watch with him at all times.

Anyone who buys the watch unsuspectingly will be happy about the good deal for the rest of the evening. That brings us to the next feature of the approaching Venetian night: the noisy, uninhibited, carnival-like happiness of its northern guests, who descend from the highest levels of barbarian society almost a thousand years ago when they invaded Italy.

Karneval in Venice!

It takes place all summer long. Every stranger buys a hat that they only use during the carnival. One night in Venice can make one’s nightmares a reality!

In the canals, densely packed gondolas fill every route, except for the Grand Canal, which usually is free from traffic. Also, if large tourism companies rent a dozen gondolas, a five-man band was distributed across the boats, and they would push through the canals like a united armada, crushing whatever stood in their way.

Inspired by the Chianti, every German woman believes herself to be the next Maria Callas, and every man believes himself to be Mario Lanza. Massive loudspeakers blast the latest hits into the Venetian night at a rate of 95 db. All the happy patrons of the bars, all the passengers in the gondolas, and all the pedestrians join in song, and it’s a wonder that the people on the bridges and in the palace don’t participate as well. I believe the danger of Venice being destroyed by sound-waves is far more realistic than the commonly-cited danger of the waves made from the wakes of motorboats. However, there is a third, less recognized danger: German card-players slamming their cards down so hard that they shake the foundations of the city. Many visitors to Venice pay homage to this beautiful game in the evening, when there is no longer enough light to take photos.

An enormous exhaustion is achieved under the constant nagging of the caring wives: “Don't drink so much, tomorrow you have to drive over three hundred miles!” Before the festively illuminated guests march into their quarters beyond the Alps while singing a traditional drinking song, the waiters repeatedly assure us when handing over the bill that the Germans are “molto simpatico,” i.e. very friendly. This determination means, in my experience, that they expect us to make no trouble over matters of making change.

On Sunday morning, it is customary to buy the most necessary souvenirs. Many people even decide to buy a book on sightseeing in Venice to peruse at home and see what they didn’t see.

As noon approaches, they all begin to make their journey in reverse on the “Weekend Crusader’s Race.”

The first German in uniform they see at the Mittenwald checkpoint makes the feeling of security return to their breast that they lose when leaving their borders, even if they wouldn’t admit it to anyone else.

In conclusion, a weekend in Venice is only comparable to Oktoberfest in Munich, and you can’t expect higher praise than that from a German.