On Neil Cicierega, Part One

Dear Reader: This month I’ve decided to pitch a piece of work to the editors of the 33 1/3 series from Bloomsbury Publishing. I consider this a bit of a longshot for a handful of reasons, not least of all the fact that this would be my first traditionally published work (not for lack of trying). Through my loss of self-confidence, you will gain a look into a fairly significant piece of cultural criticism, Dadaist art, and the world of music in my lifetime. The paid article for this month will be a five-page excerpt from a chapter I’ve sketched out roughly as chapter four, entitled “What a Concept,” about the band Smash Mouth and its place in the world in the late ‘90s vs. the 2010s and onward. Am I taking a joke of an album too seriously? Perhaps. If any of this does make it to print, though, expect it to change as I interview different people involved in the production.

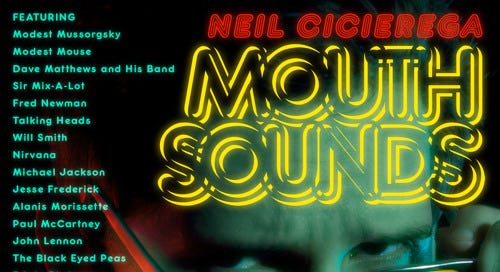

If you look hard enough for his fingerprints, some of the biggest cultural moments of the internet throughout the 2000s can be traced back to Neil Cicierega. The “animutations” he created in Adobe Flash popularized sites like Newgrounds, and viral video series like “Potter Puppet Pals” brought internet traffic to YouTube. Although he began releasing music onto the internet as early as the year 2000, it wasn’t until 2014 that he innovated an entire genre.

The idea of the “mashup” predates Cicierega by decades. Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album remains a prominent example in the genre both because of its artistry and its complete, unified thesis that Beatles songs would sound pleasing to the ear when combined with Jay-Z’s lyrics; other mashup artists tend to choose what music they use on a track-by-track basis. Cicierega’s innovation, then, comes from the dissonance that his songs create. The central, unifying motif in Mouth Sounds is Smash Mouth’s 1999 Grammy Award-winning hit “All Star.” Why? The song is no masterwork of composition, but rather a summer tune whose ubiquity during a period of turmoil in American culture not only on the radio waves, but also in film and TV rooted it in the minds of the youth. Box office hits for children like Mystery Men (which serves as the basis for its music video), Big Fat Liar, and of course Shrek all featured the band in prominent moments because at the time they were hardly displeasing to the ear. Just as “Fortunate Son” by Creedence Clearwater Revival retrospectively became the anthem of the Vietnam War and “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” shows up in any film set in the 1980s, “All Star” has become linked with the moments of history surrounding 9/11; on the one hand being a hit from the ‘90s, on the other as a visage of forced happiness in a time of great fear. Of course, this overuse eventually turned the public perception of the song from a poppy hit to an aggravating earworm that everyone would prefer to forget.

Cue Cicierega. In a move some have labeled as purely dadaist in nature, Mouth Sounds picked out tracks among the most popular of their era and genre and mashed them up, either directly utilizing Smash Mouth’s music or borrowing elements from the track “All Star” as leitmotifs. For example, the opening piece “Promenade (Satellite Pictures at an Exhibition)” does not feature the harmony, the rhythm, or any musical element from Smash Mouth’s composition, but rather varies the first word sung by Steve Harwell (i.e. “Some”) in pitch to match the trumpet melody of Modest Mussorgsky’s “Promenade,” eventually adding the words “Hey Now” and the whistling to mimic the other instruments. Another common tool in Cicierega’s shed is the use of “plunderphonics,” or re-arranging spoken lyrics to create new words entirely. In Mouth Sounds it shows up crudely in “Vivid Memories Turn to Fantasies,” and “Piss” off Mouth Silence takes it a step further, but by Mouth Moods he’s perfected the technique as evidenced by both “Wow Wow” (which also centers on a Will Smith song) and “Bustin’.”

Of course because of U.S. copyright law, this album could not have been released through conventional channels. Many indie bands have taken advantage of Bandcamp’s distribution services, but Mouth Sounds would not exist without alternative revenue streams. Whether the work done to transform the music suffices to pass under fair use regulations is not a matter that record companies are willing to advocate for in court, especially because those same companies are also the ones he has borrowed from. Instead, the entire project sits on Cicierega’s personal website, free to download in its highest quality format. People are free to donate to him in exchange for these files, but even a moderate amount of viral attention would have allowed him to recoup the cost of his time through ad revenue on YouTube or SoundCloud. This is not an innovation–many musicians on that website have skirted the line between parody song and outright ripoff before, but they tend to include visual elements (i.e. a skit as part of a music video) to supplement the music as well. The success of Mouth Sounds and its sequels laid the groundwork for other experimental music projects on the internet such as SiIvaGunner, DJ Cummerbund, and Gyrotron.

As the old idiom goes, there is nothing new under the sun. It took a long time for the broader American culture to accept the practice of sampling in hip-hop as a transformative method of music production, and the “Soundclown” subgenre is the next logical movement up from record-scratching. If we liken the former to a mosaic, in that small shards of others’ creations are rearranged as different elements to form a new piece of artwork, then Cicierega and his contemporaries are undeniably Dadaists. The original elements used to create these pieces of music are immediately recognizable to anyone familiar with them, but the artistry comes from their recontextualization. The sensations that listening to “Bills Like Jean Spirit” creates, for example, is neither comparable to “Billie Jean” or “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” nor is it somewhere in the middle. Instead, it conjures up feelings of disgust and confusion on first passes, then ire at its existence on later ones, until the listener accepts the genre for what it is and can truly weigh it against other mashups.

Why am I in a unique position to write about this album? While it may be that an account exists on Soundcloud that hasn’t been updated in nearly a decade with views in the hundreds, I wouldn’t put my sophomoric experiences forward as the driving factor behind my desire to begin this project. I believe there is a generational gap in music that needs to be bridged both between Gen X and Gen Z, but also Gen Z and whatever we designate those to follow. News stories have come out about how children are struggling with computer skills that people in my age group take for granted because of the level of technological advancement we grew up with. By-and-large, we’ve also been the ones who have taught vast swaths of older generations how to keep up with newer developments as well. There’s a “sweet spot” between Millennials and Gen Z who remember what’s now called analog technology, but also grew up alongside specific innovations so that we remember what it was like without them. This is inherently true for all time periods, so I don’t plan on framing these matters in terms of a generational divide, but I think it is our turn to capture observations about the world we grew up in as part of the historical record. Moreover, I think giving readers a perspective on the way this genre came to be will demonstrate how genres begin to form in the first place. Putting new instruments, in both the broad and the specific definition of that word, into the hands of creative-types will inspire them to try all sorts of different things. Eventually someone will come up with something that sounds good.