Book Review: Amiculus by Travis Horseman

Looking into a recent graphic novel that retells some aspects of the end of the empire.

Truth be told, I could point to half a dozen eras and areas of the ancient world that I’d like to talk more about on this website, but the palace intrigue of the 4th and 5th centuries is so much more entertaining than most people realize. Gore Vidal’s Julian had some of these qualities, but there was less of an emphasis on the paranoia over betrayal than the overall message about religion. The Amiculus comics cover approximately the same time period, while delving deeper into this theme.

The premise that there could be some conspiracy around how we don’t know what happened to Romulus Augustulus after he was deposed is a little far-fetched. The adage that “history is written by the victors” is an easy adage to gesture towards, but the fact of the matter is that historians record great moments over little ones. Though Augustulus holds the title of “final Roman emperor in the West,” the fact of the matter was that his claim to the throne was as a usurper and with his father controlling all the decisions from behind the scenes. Whatever “actually” happened isn’t likely to be half as interesting as what Horseman depicts between these pages. Is this inaccuracy forgivable? I think so; the reasons behind this stretching of the truth are necessary for the broader message of the work to get across. Monastic life would have been a pretty standard form of exile by that point, so the author surely makes the most out of this creative decision.

Another creative decision that others may regard as an anachronism but I thought was done quite well was the status of the architecture in the settings. It can be tempting to use the squalor of a crumbling city street as a visual metaphor for the moral decay in the leadership (in this case, Orestes), but Caracuzzo limits the shattered marble to scenes of siege warfare and inside Amiculus’ throne room to represent his damaged psyche. It’s important to remember that even though Rome wasn’t in a golden age like it had been centuries prior, it was still a major city and therefore an economic hub for trade.1 There wouldn’t have been any new massive public works like a second Colosseum on the budget, but the Romans would have maintained their houses from the elements better than I’ve seen in other artists’ depictions.

The architecture is hardly the only aspect of the art in this book to rave about. The use of shadows to accent the emotions on characters’ faces is masterful. One particular scene depicts a monologue where many soldiers are being led to a trap through a torch-lit hallway that’s exemplary of how one ought to work with the element of darkness. The muted color palette of greens and yellows lends to the creepiness of the situation, and it juxtaposes nicely with the gray-blues of the flashback scenes that that character relates in his own story. The only additional hue that occasionally marks these panels are bright streaks of vermilion2 that shoot out any time someone has been stabbed. Full color returns as soon as a guard throws open the door in front of them and reveals the treachery at hand.

We recently discussed some of the causes of the fall of the Roman Empire, and I’m not sure how I feel about the wholesale excision of the wider political situation in the East as it regards Odoacer’s motivation to overthrow the empire. Whereas the previously mentioned inaccuracies have been understandable in service of the plot, leaving out Zeno as the impetus for the fighting in the first place may leave the reader with a misunderstanding of the real events of history. It’s hard to get into the reasons behind why this doesn’t work without spoiling the plot, but portraying Odoacer’s rise to power as his independent decision would make it confusing to casual students of history why he ends up fighting with Theodoric 9 years later. A significant amount of the ending hinges on the concept that Odoacer has good leadership qualities that would not lead him to seek excess power. Suffice it to say that declaring himself king was not in line with the actions of the Odoacer we encounter in this book.

This marks off another medium that we have yet to conquer across the lifespan of this blog. I consider it lucky that I happened to find this by scanning through Kickstarter’s first few pages of results for new projects and hadn’t encountered this one, but the one they had done for the upcoming sequel. In addition to Pythia coming last fall, there’s a one-off comic about Trajan’s forces battling vampires in Romania called In Noctem from the same team. All three volumes of this work (N.B., I bought the omnibus edition) received accolades directly from Kickstarter as notable projects on their website, and the care and creativity show precisely why this is well deserved. Based on certain language on their website’s news page, it seems as though the Amiculus team has many more graphic novels planned for the future, and I am eager to read any future comics they put out. One star.

Money never really “stops” moving in and out of Rome. That’s where the pope is, after all.

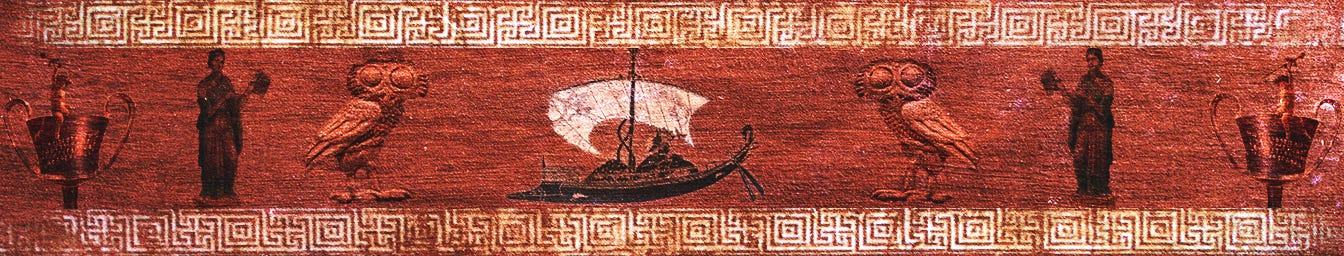

This is another unique and appreciated stylistic choice. For whatever reason this color stands out a lot more than the regular dark, crimson reds that artists use for blood. It might have something to do with how ubiquitous that pigment is in Roman art in general, but I haven’t thought all that hard about it.