Fixing 6 Problems with the English Language

A proposed grammar reform for the modern age.

In Ancient Rome, grammarians like Quintillian used to make intentional efforts to clear up confusion, and discern whether a colloquial usage of a word was more precise, efficient, or beautiful than prescriptive grammar rules would otherwise suggest. Germany still maintains some centralized planning around their language through the Council for German Orthography, with the most recent major reform happening in 1996 (although some changes were rolled back in 2006). English is well overdue for similarly intentional design reforms, six of which I have proposed below.

Datum vs. data. “Datum” is a Latin singular noun meaning “gift,” and “data” is its plural form. If I were to guess, a larger percentage of English majors across the United States insist that we ought to say “the data show this” instead of “the data shows this” than Classics majors. If we were in Ancient Rome, though, it would still be confusing to say “the datum shows this” because 3/4ths of the words in that statement are in English. Language changes. One of the examples from Caesar’s grammar books that survive to the modern day is that the word “harena” should only ever be used in the singular; the English word “sand” is treated similarly. I think that the word “datum” is wholly archaic and the word “data” acts perfectly well as a sort of collective noun. When someone says “Oh look, my wife got her hair cut,” we expect that when we turn around, the woman standing in that direction will have all of her hairs shortened, rather than just one. The other issue at hand is that the people who correct this mistake do not apply the principle consistently. We visit “museums,” and “aquariums” not “musea” or “aquaria.” Don’t even get me started on octopodes.

Bring the word “whom” back into the common parlance. It’s not that hard, especially with the modern focus on pronouns as a cultural battleground, to use “whom” in any place where “him” or “her” or “them” would otherwise be appropriate? “To whom was the present given?” “Well, I gave the present to him.” It’s so much harder to learn languages with a case system if we don’t emphasize the remnants we have in our native tongue. I’d also like to proselytize on behalf of “whither/thither” and “whence/thence,” but that’s certainly a losing battle in the 21st century.

democratic vs. Democratic vs. Democrat. A democratic system is one that the deme (i.e. the common people) has authority in; its opposite is autocracy. A Democratic government is a system where the people are the governing body. There’s an old pedantic chestnut that people use when someone claims that “democracy is at stake” where they’ll smugly say “actually, we live in a constitutional republic.” This is silly for two reasons; the first is that constitutional republics are democratic systems, and the second is that the word “constitutional" is doing nothing in that statement. All modern governments across the globe have some form of constitution, so using it as an adjective does not disqualify any real systems. The USSR had a constitution, as did the Roman Empire and Germany under Nazi occupation. A Democrat is someone who caucuses with the Democratic party, which is a term that has as little to do with either of the prior terms as the Republican party does with upholding the so-called Republic. We live under an oligarchy;1 whether this is because of a fatal flaw in our constitution or by design is a matter for modern historians to quibble over, but the fact of the matter is that candidates need the backing of at least one wealthy party to be able to run for any office with meaningful power. The interests of the upper class are protected before any other class, and any action taken against them has been swiftly voted down. In an effort to differentiate between democratic systems and a Democratic government, I believe the term “commonwealth” should come back into vogue to replace the former. Four states and two U.S. territories use that word in their constitutions to describe themselves, but it holds no consistent definition across them.

Modern and “postmodern” as stylistic descriptors. Modern is a synonym for contemporary in every context except for the humanities. For something to be “postmodern” it would have to not yet exist. If you told an alien that modern literature faded out of popularity after the ‘60s, they’d probably zap you for trying to make a joke at their expense. I assume whoever came up with those terms must have been in a doomsday cult, because there’s no other reason to label yourself that way than believing that it would be the final development. Whoever decided that “Generation X” was a chronological label instead of a signifier of an unknown quality2 was similarly ridiculous; we’re lucky that millennials rejected the less popular “Gen Y” moniker, but what’s supposed to come after Gen Z? Postmodern isn’t even the worst of the post-Modern styles that artists have had to come up with names for; we’ve got neomodern, remodern, metamodern, and even post-postmodern art.3 Pretty soon we’ll have to have for-real-this-is-the-latest-modernism. I am someone who giggles at the mention of “antepenultimate syllables” because I find it silly to have to use such a big word to say “third-to-last,” but the longer we let this go on, the more modifiers we will have to tack on to the word “modern” to differentiate distinctive styles. We could use the term “neo-skepticism” to replace postmodern thinking to emphasize some of the discipline’s rejection of prior structures of presentation. For literary postmodernism, I think that “supratextualism” would sufficiently describe the movement because of how much the reader must understand outside what has been printed on the page.

Antagonist vs. Protagonist. I already seem to have lost this battle in my own mind because I debated whether to knowingly use the incorrect word intentionally for clarity’s sake in my essay on Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God a few months ago. “Protagonist” uses the Greek prefix πρώτο-, meaning “first,” to define the main character of a story or play. The antagonist is someone or something that works against the protagonist. Most fictional works follow the perspective of a good guy who fights against a bad guy, which has allowed the term protagonist to take on a connotation of benevolence. Alex is the protagonist of A Clockwork Orange, Humbert Humbert is the protagonist of Lolita, Tyler Durden is the protagonist of Fight Club,4 and Patrick Bateman is the protagonist of American Psycho. This misinterpretation works both ways; some also assume that authors who write evil characters as their protagonists mean to uphold their actions as morally good. In the case of the former pair, critics have failed to pick up on deeper themes and labeled the works as monstrous, while the latter pair of fictional characters have had a cult of personality built around them full of teenagers who are too scared to talk to women. If we respect the original definitions of these terms, more people will inevitably be open to properly interpreting media.

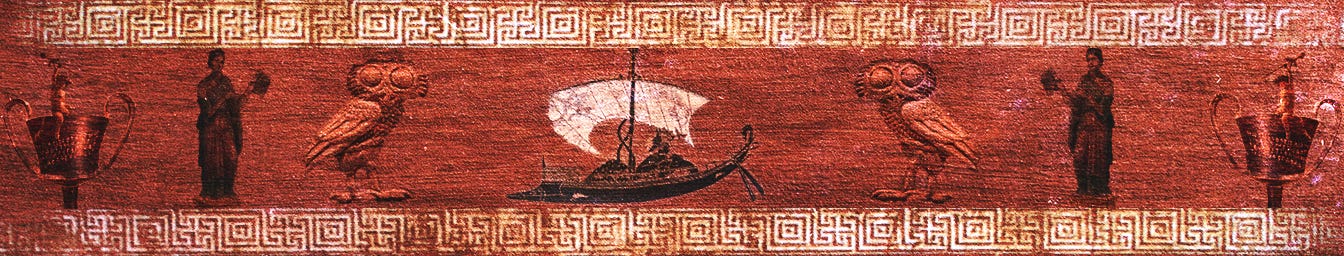

The classics vs. “an instant classic.” It naturally had to end with this one, didn’t it? First of all, let’s agree that using the term “classic” in contemporary reviews is akin to fortune-telling; there’s no way for any of us to tell what will last a decade in the public consciousness. A classic, by all definitions of the word, is something that is timeless. As authors like Irving Bacheller and James Hilton fall into obscurity after publishing bestsellers, others like John Kennedy Toole gain relevance long after the decade that they wrote their novels in. We know that the classical canon is timeless because the works of Vergil, Ovid, and Homer have been translated, read, and actively discussed in every era of every major civilization after they have been introduced. The themes present in these works surpass what constrains others by nationality, gender, religion, or era. It’s very difficult to find books in any other age or civilization that can make the same claims that the Greek and Latin classics do. If it is impossible for us to limit the label of the classics to ancient works, I think that Italo Calvino’s definition is begrudgingly workable in my eyes.

We talked about oligarchies in more depth here: https://nusky.substack.com/p/in-defense-of-the-great-books

"X-ray” being the most common example.

One of these may be a lightly veiled attempt to promote neo-fascism. I’m not entirely sure. Anyway, they’re all very silly.

Okay, technically he’s also the antagonist. If you came here to argue this, you win.