Book Review: Delenda Est by Poul Anderson

A review of one novella in the Time Patrol series, set in a world where Rome fell to Carthage.

We have been due for a return to the science fiction genre in this section of the blog for quite some time now. With the intense philosophical, moral, and political nature of the last paid article, on top of the inception of work on an important project debuting next week, things have been much too serious. This isn’t to downplay the work of Poul Anderson, mind you; that name will be immediately familiar to a certain section of the science-fiction diehards. Time-travel may be an exciting trope to explore in the genre, but doing too many similar stories with that theme back-to-back will inevitably invite unfair comparison. That’s why I’ve secreted away a few hallmarks of the style in the back of my bookcase for rainy day moments such as this.

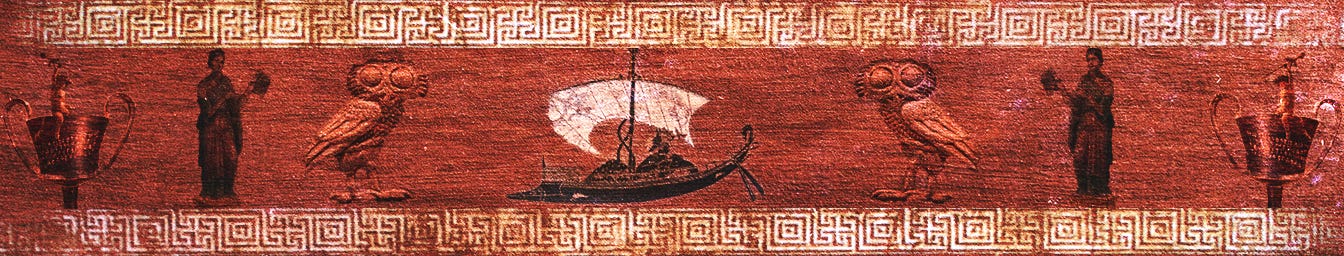

Technically speaking, Delenda Est is the second in the Time Patrol series, but the introduction broadly gives the reader all the context needed to understand the mechanics of the in-universe system and the role that the eponymous occupation plays in their world.1 Prior to the release of Back to the Future, authors weren’t really as concerned about the intricate details of the function of time travel: readers were expected to believe that anything that was done was possible, while everything that wasn’t couldn’t be done. A whole generation of nerds has been primed on string theory and the butterfly effect to believe that history is easy to change, not hard. If we view the world as a web of interconnected events, as this author does, then it makes for an altogether more interesting story. We have discussed before that there was a natural predilection for the Italian peninsula to be a font for civilization after the end of the Iron Age, whether it be native-born Etruscans, a rowdy band of Trojans having been exiled by fate, or as in this case a conquering force of Carthaginians. Holding said peninsula as a colony for more than a few years across the whole Mediterranean, though, is indeed a nigh-insurmountable challenge. The groundwork for this setting is totally sensible as it has been presented.

Consequently, this novel deals with two main themes: the prospect of a non-existent future, and what it means to transport someone from that new world into a repaired timeline. The temporal fabric can bear the weight of one person popping into existence from a prior timeline, but it’s impossible to make refugees out of an entire era without warping the world even further. Conversely, once Manse Everard and Piet Van Sarawak get to an outpost in time before the relevant details have been altered, they have to make an effort to rescue agents who have likewise traveled forward in time and would be destroyed when things got fixed. Outside of their duties, members of the patrol lead generally normal lives. A handful of unexplained deaths can meld into the fabric of history without much trouble, but beyond their feelings of reciprocity towards their peers on the force, it may have greater implications for the timeline.

The overall subgenre of alternative history has become lazy as of late. Most of the popular output has come to us in the form of “What If?” scenarios: the postulation that if a battle or major political event had gone one way, then a thousand other events would naturally follow as a matter of fact. This is, of course, preposterous to say with any degree of certainty, and is tantamount to predicting the future. Leaving these types of stories to fall under the genre of fiction is more difficult for the author, but it gives them more plausible deniability. The motivations of someone who attempts to change history in a time travel scenario like this can serve as a justification for all consequent events.2 This novella only uses two nameless goons from a far off time as the crux for the discrepancy in timelines, but the first story in the Time Patrol series has two examples of great characters that change history for different reasons. The first is a traditional megalomaniac archetype, and Manse Everard has to play to his ego in order to outwit him before things turn sour. The second is more complicated. A fellow employee of the patrol goes rogue and seeks to rescue his dead girlfriend from the Nazi blitzkrieg in England. Things naturally work out differently when someone reasonable can be negotiated with.

Not only is this a better mode of the author’s expression of ideas, but it also makes for a better experience for the reader. Rather than presenting a litany of data and charts to back up a hypothetical position on a given scenario, the narrative structure allows an author to propose an idea without having to justify every little detail. If, for example, an author would want the Spartan wing to survive the slaughter at Thermopylae, it would be much easier to have a well-armed time traveler cut a path through the Persian forces than it would to justify how a force of 300 men could do that on their own. In the previously reviewed novel Lest Darkness Fall, L. Sprague de Camp leaves off just before things even begin to change with history, and is able to get away with vaguely gesturing that life will be better for the Romans without any necessary justification in the eyes of the reader. The 2nd Punic War is broadly regarded as the closest anyone got to sacking Rome between Brennus and Alaric, so Poul Anderson’s readers are already primed to believe this alteration as plausible, but 25th century weaponry certainly doesn’t hurt the case either.

Constraining one’s heroes to preserve the established historical timeline additionally presents its own struggles that make for a compelling narrative. When facing the previously mentioned 25th century weaponry, the Time Patrol would risk discovery in the wider world if they used similarly anachronistic weaponry. Part of their introductory training requires them to be hypnotized into never revealing the existence of the patrol to outsiders, so this is a de facto part of their business, and the decision has already been made for them. Therefore, they must approach all situations at a disadvantage, and make up the gap with superior planning and intelligence. In that sense, there are a few similarities to Fleming’s Bond novels, and it certainly benefits from the same development of suspense. The way that Poul Anderson presents his vision of a Rome-less future also helps to build an idea of what he credits and blames that civilization for. On the one hand, Deirdre being a trusted member of society in their equivalent of the 20th century gives some evidence that equality between the sexes had been accepted throughout most of history as a given. This suggests that Rome’s treatment of women is partially to blame for our own tradition of sexism. On the other hand, slavery is still a common practice and they never really figured out technology, to the point where they were using blimps as machines of war. We’ve talked about Rome’s impact on human emancipation before on this blog, and the Roman military was a fantastic way for new inventions to come to light.

It is incredibly easy to give this series a broad recommendation, not only because of the quality of the storytelling, but also the nature of the novella length. The plot is very tight, and it’s not a massive time commitment like the recent Vidal or Mailer tomes that have been featured in recent weeks. It’s a fun thought experiment told in a narrative form that doesn’t overstay its welcome. I’m happy to give Delenda Est one star.

I read Delenda Est first, then went back to read the introductory book on a lark. The only bit of information I didn’t pick up on was Everard’s role as a main character, rather than one from an ensemble cast.

The group in this book that changes history are an unnamed pair of hooligans with no stated motivation, but the first book in the series more than makes up for it with an interesting character.